The Institut National de l’Origine et de la Qualité (INAO), France’s official agricultural organization, has launched the first ever official certification of natural wines. There are also plans to include Spanish and Italian winemakers in a relatively short period. The scheme will run a three year trial period before it is evaluated.

Natural wines have always existed, but the activist movement emerged as a reaction against the industrialized wines that were dominating from the 1960’s on. This movement has been inspired first of all by some Beaujolais producers. For every decade it has become more popular and spread to new countries.

There is no consensus about whether this is a necessary, or wanted, step, or not. It is widely understood that a natural wine comes from organically or biodynamically farmed grapes, and has little or no additives in the cellar. There is however a continuous debate among the natural wine producers as to whether a small amount of sulphur before bottling should be allowed or not.

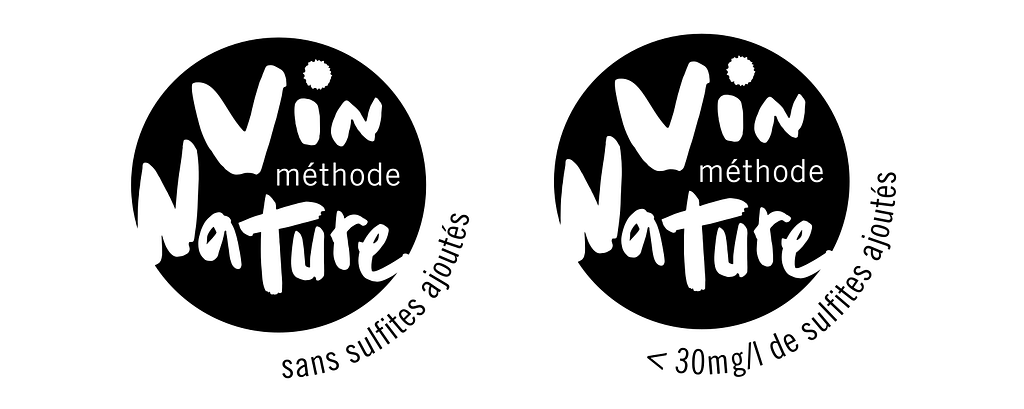

To evit going into this debate the Syndicat de Defense des Vins Naturels (an independent group originating in Loire some ten years ago but officially founded in 2019, and that has penned the new regualations), has included both views – one category for zero additions, and one for additions up to 30 mg/L of sulphites.

Writer and chemist Jamie Goode asks in the publication Wine Enthusiast 19/5, whether this is a needed, or wanted, step. He also points out that there are weaknesses. He says, “yeasts can produce varying amounts of sulfites during fermentations (…) it’s also not rare for yeasts to produce more than 30 mg/L of sulfur dioxide, which means that the wine cannot be certified”. I think that Goode is right. Here is a possible weakness, or something that can be amended: Although the intention is to allow a maximum of 30 mg, the current edition does not specify 30 mg is maximum or added sulphites.

Other than that Goode sees several positive sides. Accountability is a possible benefit, he points out, as those who use the Syndicat’s natural wine logo have legal obligations.

There are growers that finds the whole natural wine activist movement a bit strange, a bandwagon, a hipster movement of something they have been doing forever. In continuation to this, Goode also cites Doug Wregg, of leading British natural wine importer Les Caves de Pyrene (co-organizer of the Real Wine fair). Wregg says, “the certification could be used by companies simply in search of a commercial opportunity”.

Goode concludes that he “applaudes the effort, but (is) very much not sure of the result”.

One who mounts his stool to speak in favour of the new regulation is Simon J. Woolf in his publication the Morning Claret 2/4. “One of the biggest bugbears in natural wine”, says Woolf, “is the lack of organic certification amongst growers – an honour system is all well and good if one is on first-name terms with the grower, but it doesn’t help the end consumer very much. Your wine might have zero added sulphites and a funky label, but how do I know what goes on in your vineyard during a rainy year, if you decided that getting organic certification was just too much hassle?”

First he points out that it’s too easy for “bandwagon-jumpers, weekend warriors and the organic-when-I-feel-like-it brigade” to join the club only when they feel like it, and he sees this as a means to make it more difficult for those who are not fully determined.

And regarding the differing opinions within the natural wine producers, Woolf sees no problem. “It is important to note that the labelling scheme is entirely voluntary. Winemakers working within the natural wine oeuvre are not under any obligation to apply for the label, or to change the ways that they currently produce or label their wines.”

Woolf points out that, “the biggest clue that a scheme like this is required is that it’s been instigated and hard-fought over by winemakers themselves”. An appropriate example is Sébastien David himself, who had his Coëf 2016 Cabernet Franc confiscated and destroyed (!) by the Bureau d’Invéstigation de Enquêtes Vinocoles (BIEV), because of too high levels of volatile acidity. The laboratory results were also debated by David. As Woolf continues, “the new charter would not necessarily have saved David’s wine, but one can understand him wanting to have at least one system which is on his side”.

Woolf concludes: “The approval of this charter is a massive step towards more general acceptance of natural wines, as a valid segment of French wine. They are no longer just something just to be legislated against, but now have a seat at the table.”

Hannah Fuellenkemper, also in the Morning Claret 21/4, lists some points of what could be considered after this: Water imprints (who are recycling?), the use of plastic (and throwing it away), bottling (is it always necessary?), transport (does a winemaker deserve the karma of an organic winemaker when most of his production is trucked around the globe?),

What do I think? It seems to me that Simon Woolf has put must valid arguments on the table, and I hope this can speed up the process of recognition of natural wines (that I think will come anyway, in the end). Still, like Jamie Goode, I doubt that these regulations will have a great effect. Because the spirit of the natural wine movement is that of freedom, not regulations. They will get acceptance in the end, same as the environment activists, but they will take it further towards a world where a holistic view reigns supreme.

[…] David and Marianne Koeberle took over the family’s 27 hectares of vineyards in the village of Saint Hippolyte in 2005. They converted early on to organic and biodynamic practises. The latest years they have taken further measures too meet the strict demands of the Vin Méthode Nature (see article about certification of natural wines here). […]